Postcards from Pakistan

Postcard from the Karakoram Highway ‘life is a journey not a destination’

We are driving along the Karakoram Highway from Hunza, through Skardu to Shigar in Gilgit-Baltistan. It seemed like a good idea to drive, to see more of Pakistan, to experience what has been described as the eighth wonder of the wonder. I also wanted to continue our journey along the Old Silk Road.

This section of the Highway is 325 kilometres and according to Google maps will take 7 hours to drive. Our guide mentioned it was more likely to take 8 to 9 hours depending on road conditions and road works.

The Karakoram Highway, also known as the China-Pakistan Friendship Highway is 1,300 kilometres in length and starts in Hasan Abdal in the Punjab Province and ends at the Khunjerab Pass in Gilgit-Baltistan (the subject of a previous blog). Started in 1959 and finished in 1979 it is one of the highest paved roads in the world. From the Highway you can see three mountain ranges, The Hindukush, the Himalayas and the Karakoram. As part of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor the Highway is being upgraded. In the building of the Highway 810 Pakistanis and over 200 Chinese workers have lost their lives due to extremely difficult working conditions.

I had been told that the journey along the Highway is spectacular but also that the road conditions can be very difficult. Work to upgrade this stretch of the Highway is underway, with impossibly large equipment scattered along side the road. The Highway moves from a single paved road to a double paved road (it still looked like a single road to me), to gravel, and back to being paved again. Landslides are a common occurrence. A large portion is still gravel, with no guard rail and a steep drop to the valley below.

Being forewarned didn’t prepare me for how difficult parts of the road were to drive along. The single laned parts of the Highway made me grip the handle of the passenger car door and breath in when cars and trucks tried to pass. The gravel threw up lots of dust and at times it was difficult to see the road ahead. When a truck broke down on a tight, single lane, hairpin turn I thought we were in for a long wait. I was more horrified when our driver decided to edge slowly around the truck. Local workers were extremely helpful helping us navigate around the truck, but I was then also concerned for their safety.

When the road widened and was smooth, I could sit and enjoy the passing scenery. We would turn a corner and in front of us would be the most beautiful green valley with neat terraces climbing high up the mountainside. We would turn another corner and see mountains rising high above us. Another turn brought back my fears as I saw the remains of a large landslide flowing down the mountain. One of the most spectacular sights was Nanga Parbat, at 8,126 metres. Nanga Parbat stands at the western end of the Himalayas, it is the ninth highest peak in the world. There are fourteen mountains in the world that are 8,000 metres or higher, five are located in Pakistan.

There is a quote, attributed to Ralph Waldo Emerson, that ‘life is a journey not a destination’. The Karakoram Highway is a spectacular, if somewhat terrifying, journey.

Leaving Hunza

Nanga Parbat in the far distance

Nanga Parbat a little closer

Part of the newly sealed Highway

Stopping for a rest and watching the trucks and vans drive past

Small truck about to leave to continue their journey

The dusty edge of the Highway

Road workers taking a break

Small tents along the Highway to house workers

So much dust it was hard to see the road

Trucks approaching

My view of a truck from my passenger seat

The dusty road winds on

Landslide, thankfully across from the road

Goats ignoring the stop, blast area, sign

Zig-zag path of the Old Silk Road

Rocks, stones and dust

The edge of the Highway. The strings you can just see are mapping out future road works

Building a retaining wall and bridge

New retaining wall and man hanging off the back of a small truck

Still hanging on

Suddenly it turns green

Amazingly green fields after hours of dust

Skardu Valley, where the Indus and Shigar rivers meet

Postcard from Passu - a glacier, a cathedral, a bridge

After leaving the Khunjerab National Park we head back to Hunza, stopping in Passu. Pakistan has over 7,000 known glaciers and contains more glacial ice than any other country outside the polar regions. Pakistan has a population of over 220 million people who rely on glacial water for drinking water and farming. However, Pakistan’s glaciers are receding. Rapid glacial melt has lead to flash flooding, avalanches, landslides, destruction of infrastructure and loss of life.

In the south of Passu is the Passu Glacier. This glacier links up with a number of other glaciers in the region. The Passu Glacier is 20.5 kilometres long, spread over 115 square kilometres. Behind the glacier sits Passu Peak at 7,478m.

The view from the road is breathtaking, on the left is the Passu Glacier and on the right is Tupopdan, also known as Passu Cones or Passu Cathedral. This mountain range stands at 6,106 metres above the Hunza River. Tupopdan is the local name for the mountains and it means ‘sun gulping mountains’ but as we were there on a very cold and overcast day I will have to believe the locals. The sharp peaks made me think of a sleeping dragon, but I could also see the reference to cathedral spires.

We had also stopped in this area to see and perhaps walk across the Hussaini Suspension Bridge. It is a pedestrian bridge that crosses the Hunza River so you can walk to Zarabad Hamlet from Hussaini Village. The Bridge has been washed away a number of times due to flash flooding. It is made of wooden planks, some narrow, some wide, each plank is set at a different width to its neighbour making it very difficult to walk with confidence. It also moves up and down as other people cross the bridge and swings side to side in the wind.

I slowly stepped out onto the bridge, it moved slightly side to side, I kept walking and when someone walked closely behind me the bridge moved up and down and I felt like I was on a trampoline. I waited until they had passed by and kept walking, slow by slow step, holding tightly to the metal wires. As you move further along and further out over the river the bridge moves a lot more, but I was gaining in confidence and started to walk a little bit quicker. I made it to the other side and was feeling pleased with my daring walk only to see two locals quickly walk across the bridge without holding on! I was so fascinated with their progress I forgot to take a photo of them.

I turned around and walked back across the bridge, I was happy to have walked across and even happier to be back on safe, non-rocking ground.

On the far left is Passu Glacier with the Passu Cones in the centre

Passu Glacier

Tupopdan, also known as Passu Cones or Passu Cathedral

Our first view of the Hussaini Suspension Bridge

Looks much longer up close

Ready to start

View from the opposite bank

Steps leading up to Zarabad Village

Some thick planks and some exceptionally thin ones

I’ve made it back!

Postcard from the Khunjerab Pass

The road disappears under snow and ice

We are driving 182 kilometres from Hunza at an elevation of 2,438m, along the Karakoram Highway, to the Khunjerab Pass at the Chinese Border. We will be driving through the Khunjerab National Park at an elevation of 5,200m. The upgrading of the Karakoram Highway is part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.

Our first stop is at the exceptionally blue Attabad Lake. The lake was formed in January 2010 as a result of a landslide. Twenty people were killed and villages disappeared under water. The Hunza River was blocked for five months. The Karakoram Highway was moved and five tunnels were built named the Pak-China Friendship Tunnels. The longest tunnel is over 3,000m. Today the Lake is used for boating and fishing.

After the tunnels we enter a world of muted colours, of grey rocks and skies, of white snow and blue ice. I am surprised at how quickly the landscape changes, it seems that winter is still here. I find the stark landscape very beautiful, but the winds are bitterly cold.

We have been told that the Khunjerab National Park is open to visitors and we should be able to make it to the border. However, we are warned to be extra careful as the day before a 4WD had come off the road. As spring comes to this region the snow melts and ice forms making the roads dangerous.

The National Park is known for its wildlife: yaks; snow leopards; Marco Polo sheep; ibex; marmots; lynx; wolves; foxes and numerous birds. It covers an area of over two thousand square kilometres. There are some trees that seem to be able to flourish in the snow: juniper; birch; willow and poplar. Trees soon give way to low bushes and then low grasses. We stop and watch herds of yaks move slowly, looking for grass. They don’t mind having their photo taken. The ibex are lot more skittish and run and jump out of our way.

We drive slowly up the winding road that is wide and well maintained. Soon the road becomes difficult and disappears under snow and ice. Within two kilometres we give up hope of reaching the Chinese Border. The snow is too thick, and we can’t see the edges of the road ahead. Time to turn around and head back to Hunza. On the way down we see a flash of orange. I think it is a fox, but we are told it is a golden marmot, a lucky, rare sighting. We watch as it moves with surprising speed across the steep and icy slopes. On the way home we stop at the Hussaini Suspension Bridge, the subject of my next blog.

We return to the mild, green, and blossom filled Hunza Valley. It has taken a day to not reach the Chinese Border but it has been another day filled with adventure, beauty and wonder.

Attabad Lake

One of the Pakistan-China Friendship Tunnels

As we pass through the tunnels and come out the other side it feels like all the colour has been removed from the landscape

A photo opportunity for Geoff to wear the local cap and scarf, both are made from wool, both are very warm

There are a small number of suspension bridges crossing the Hunza River, this one is for cars

We watch as the black 4WD crosses over the bridge

We stop so I can photograph these beautiful Birch trees

Unconcerned Yak

He lifted his head and seemed to say ‘take my portrait please’

Ibex

What you don’t want to see at the side of the road

We stop for a very quick selfie and then jump back into the warm car

Golden marmot

Postcard from Baltit Fort

When you first arrive in Hunza you can see Baltit Fort sitting high above the valley with a wondrous backdrop of snow-covered mountains. It is close to Altit Fort (the subject of my previous blog) but where Altit sits next to the Hunza River, Baltit Fort seems to float in front of the mountains and the Ultar Glacier.

Be ready for a steep climb through the town of Karimabad to reach the entrance to Baltit Fort and then be ready to climb more steps to get to the front door and yet more steps inside. The effort is worth it. Baltit Fort is an impressive building with even more impressive views of the whole Hunza Valley.

The site was obviously chosen for its strategic importance for security, water and trade. The Fort was built 700 years ago on a flattened rock spur and floors and rooms have been added over time. Notable changes came about in the 16th century when the local Mir (king) married a Baltistan princess. As part of her dowry renovations were made by Balti craftsmen and you can see Tibetan influences in the shape of the ceilings and on door supports.

In my last blog on Altit Fort I wrote about two princes, Prince Shah Abbas and Prince Ali Khan and their disagreement that led to the death of the younger prince. Prince Shah Abbas made Baltit Fort the new seat of power for the region. It remained the palace until 1945 when the Mir built a new palace close by.

Left empty and in need of serious repairs there was concern that the Fort would become a ruin. Six years of renovations were completed in 1996 by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture. The renovations have been done exceptionally well and have kept the original feel of the Fort. From the soot stained and charred ceilings in the kitchens to the colourful mosaic windows open to the cool wind from the surrounding mountains you can start to imagine what life must have been like here.

Baltit Fort at the foot of the Ultar Glacier

Baltit Fort sits on a flattened spur of rock

Walking past traditional houses in Karimabad

History around and above every corner

Water was and still is a valuable resource. Water channels were built across Karimabad

Side view of Baltit Fort with clear lines of wood and stone

Just a few more steps to get inside the Fort

Local with traditional woollen Gilgiti cap with shaati feather

Maintenance of Fort and surrounding buildings is hard work as all stone has to be carried by foot

Cannon from 1863

View of Hunza Valley from top terrace

Tibetan inspired ceiling above the kitchen

Centuries of soot and smoke

What do you think this box was used for?

Ceiling detail

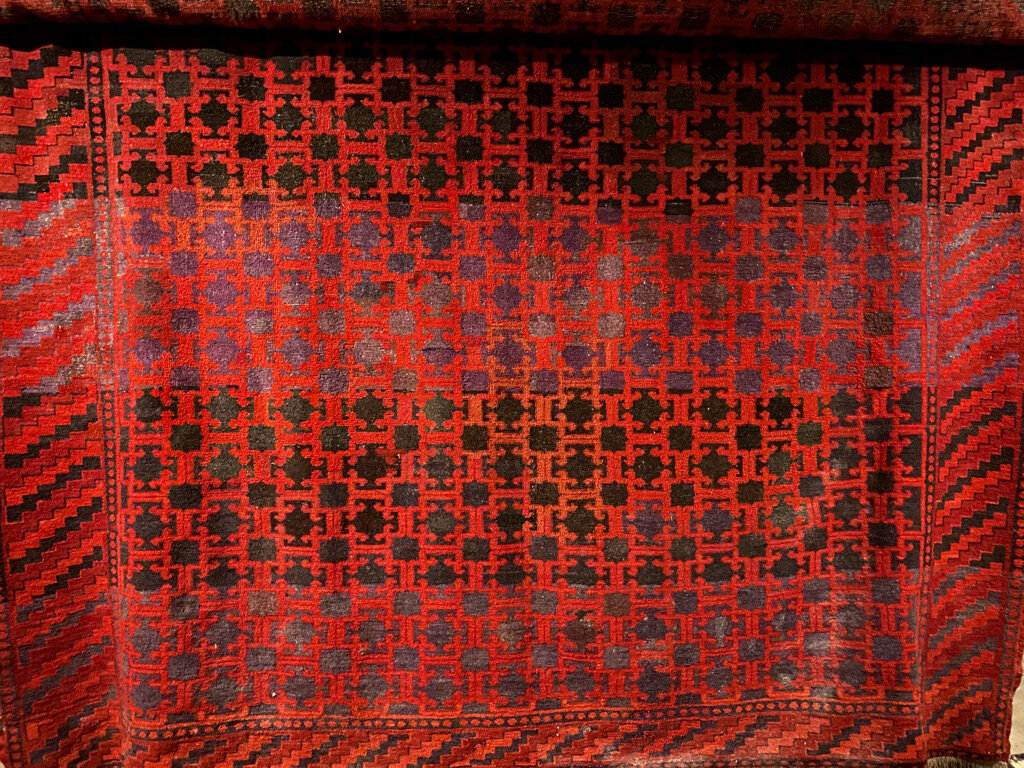

Traditional Hunza woven rugs

In the mid ground you can see Altit Fort

Postcard from Altit Fort - a thousand year old fort with a thousand foot drop

As you can see from this photo Altit Fort sits high above the Hunza River. There is a straight, 1000 foot drop from the fort to the river below. The Fort started as the traditional home of the local Mir, or king. It sits in a strategic position overlooking the Ulter Glacier and the Hunza Valley. The Fort’s prime position made sure that the Mir was ready against attack at all times.

The Fort has been wonderfully restored by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture and the Norwegian Government from 2006 to 2010. The Fort is built of wood, stone and mud. The use of alternating wood with stone made it able to withstand earthquakes. Looking up at the Fort you realise that it would be difficult to build today, let alone 1000 years ago.

Inside the Fort you can find rooms with furniture and belongings giving an idea of what life might have been like for the Mir and his family. Each room has intricately carved door lintels and window shutters. Doors and ceilings are low, windows are small to keep in the heat.

The Fort has a fascinating history revolving around princes, politics and pillars. Around 1540 a new fort, Baltit Fort, was built in Hunza (the subject of my next blog). Prince Shah Abbas moved to Baltit Fort, and it became the new capital of Hunza. Prince Shah Abbas’ younger brother, Prince Ali Khan, remained at Altit Fort. The two brothers fought and it is believed that Prince Shah Abbas buried his younger brother alive in a pillar in one of the rooms in Altit Fort. This is not the only story of death at the Fort. Altit Fort has one tower ‘Shikiari’ or ‘Hunters Tower’. Prisoners were held in dungeons and sentencing could involve being thrown from the tower over the cliff.

However today you will find it a peaceful place. After spending time looking around the Fort you can enjoy a walk through the beautiful gardens and stop at Kha Basi, a former Mir’s winter residence, now a café with great views.

As we were walking around the garden, we heard some wonderful music. Set in a corner of the garden is a music school where students can learn to sing and play traditional Pakistani instruments. We had been walking past during one of their rehearsals and were fortunate enough to be invited into the school to listen to the students play. As a bonus our travel guide and our guide from the fort got up to dance. It was a wonderful end to our visit to Altit Fort – an afternoon of history, politics, music and culture.

Altit Fort built closely around the rock base

Front door to Altit Fort

The pillar!

The kitchen

View from the top of the Fort across the Hunza Valley

Old Altit Town sitting under the Fort

Postcard from Old Altit Town

A look down on Old Altit Town from Altit Fort

A gentle walk from our hotel to Old Altit Town takes us along dusty roads, past tall poplar trees and alongside terraced farms. Land and fuel are both in short supply so poplar trees are planted because they are fast growing and don’t give too much shade over farmland.

As we walk along the road we hear a lot of shouting and clapping. As we turn a corner, we see that there is a cricket match going on. The pitch is dusty and bumpy, the bowlers fast but the batters understand the pitch and where to place the ball. Around the edge of the pitch there is a wall that is terraced, local men and boys are sitting and encouraging their favourite players. We stop and watch for a while. We are asked where we are from and the answer of Australia brings smiles for another cricket loving country. Sign language helps us understand where the boundaries lie: beyond the trees is a six; first terrace is a four.

We continue on our walk to Old Altit Town. The town sits below and right up against Altit Fort, the subject of my next blog. As we walk through the town we see a courtyard with many women sitting around chatting to one another. They are all wearing the traditional, embroidered Hunza hat, over which they place their dupatta (scarf). Read my previous blog on the Hunza Valley if you want to see one of these hats up close.

I ask if I can take some photos. The rest of my group, all men, are not allowed in. I walk around smiling and saying hello, my Urdu is poor, they don’t know English. As I point to my camera some agree to have their photo taken. One woman points to her face and from her expression seems to say why would I want to take her photo. I nod and smile, she smiles and agrees to have her photo taken – it is my favourite portrait that I have taken in Pakistan. I would like to stay but my group is waiting, I say my goodbyes. They laugh and keep talking. After a long day working it is wonderful to see them taking a moment to sit and chat with their friends.

Green poplars, dusty roads, surrounded by mountains

Local cricket pitch - unforgiving surface!

A fellow cricket lover who was happy to help out with questions on boundaries.

Small cobbler business

Chicken shop - didn’t stay to see a purchase

Central pond in Old Altit Town. This pond freezes over in winter.

Gateway to the women’s courtyard

Language may have been a barrier but we all smiled and laughed

Old Altit Town

Looking down into Old Altit Town from Altit Fort. You can just see part of the women’s courtyard in the top, left corner

Houses made of wood, mud and mud bricks, small courtyards and gardens, flat roofs for sitting, washing and water tanks

Postcard from the Hunza Valley

Beautiful blossoms and snow capped mountains will be my lasting impression of the Hunza Valley

The Hunza valley is in the northern part of Gilgit-Baltistan at an elevation of 2,438 meters. Afghanistan is to the north and China is to the northeast. The Hunza River runs through the valley and you can still see remains of the Old Silk Road.

We visited during spring and the apricot blossom trees were in full bloom. The air was fresh, villages clean and terraces beautifully ordered. It was wonderful to walk along nearly deserted paths and hear nothing but the buzz of bees and the occasional motorbike.

In 1933 a novel by James Hilton was released called ‘Lost Horizon’. In 1937 it was made into a film by Frank Capra. The book and film are set in Shangri-La, a ‘mystical and harmonious’ valley in Tibet that is isolated and where people live for hundreds of years. It is thought that Hilton based his novel on the location and people of the Hunza Valley.

The Hunzakut were rumoured to live exceptionally long lives, to be very fit, to be vegetarian and never get ill. Unfortunately, this has turned out not to be true. The Hunzakut are very fit as most must walk to work in the fields, at altitude. During the summer they do follow a mostly vegetarian diet as the growing season for fresh fruit and vegetables is very short. Animals are kept for meat for during the long winter months. As Hunza is very difficult to reach a lot of diseases did not arrive until roads opened up the valley. As to living very long lives this depends on how you measure age. Apparently the Hunzakut do not measure age solely by years but also by wisdom.

If you are ‘wise beyond your years’ you will visit Hunza as it is a beautiful place filled with stunning landscapes and hospitable people.

Hunza Valley from Altit Fort

Hunza Valley panorama taken from Altit Fort. Hard to give you a sense of being surrounded by mountains

Hunza Valley from Baltit Fort

Snow gives way to barren mountain sides. Those squiggly lines in the middle are roads going up high into the mountains.

The Hunza River runs through the centre of the valley

Blossoms above and below

Poplar trees and patchwork terraces

A man rests and checks his phone

Pink blossoms against a blue sky and white snow capped mountains

Clouds lift and we can see the mountains from our hotel

Delicate apricot blossoms

The day ends, the sun sets, we watch the changing light on the mountains.

Postcard from Rakaposhi

Today we drive from Gilgit to Hunza, just over 100 kilometres along the Karakoram Highway. We are looking forward to seeing a number of mountains: Rakaposhi; Diran Peak; Hunza Peak; Ulter 1 and 2; and Dastgil Sar Peak.

This part of the Highway has been completed and is smooth but sometimes very narrow. There are a number of memorials along the highway to honour the workers who died building it. We stop at one memorial and meet the custodian who tells us about the workers who died building this stretch of the Highway. The inscription reads ‘In memory of their gallant men who preferred to make the Karakorams their permanent abode’ 1966-1972.

Our next stop is to see Rakaposhi, a mountain in the Karakoram Mountains about a two hour drive north of Gilgit. At 7,788m it is the 27th highest mountain in the world or the 12th highest mountain in Pakistan. Despite only coming in at 27th, well behind K2, this mountain is loved in Pakistan and we were keen to see it up close.

Rakaposhi means ‘snow covered’ locally but the mountain is also called Dumani ‘Mother of Mist’ or ‘Mother of Clouds’. We had an exceptionally clear day and there was only the faintest hint of a cloud around the summit. Ragaposhi is situated in the Nagar Valley and as we drove along the Karakoram Highway we kept seeing enticing views.

The place to get the best views of Rakaposhi is at the Rakaposhi Viewpoint in Ghulmet where we stopped for morning tea. According to the sign at the viewpoint we were at 1,950m and we could see the highest, unbroken slope on earth. The summit is almost 6 kilometres above us and only 11 kilometres away. It is the only mountain on earth that plummets directly, uninterrupted, for almost 6,000 metres from the summit to its base.

The Viewpoint has a small café and gift shop, the tea was very good, and I couldn’t resist buying a souvenir. As we were travelling during Ramadan we were the only ones there enjoying the spectacular scenery and peace and quiet.

Travelling along the Karakoram Highway from Gilgit to Hunza

Karakoram Highway Memorial

Memorial and cemetery custodian

Seating area next to memorial

We are driving alongside the Hunza River

Beautiful vistas keep opening up

The milky green of the Hunza River

Roadway on other side of the valley, tall Poplar trees along each ridge

Down below in the valley, terraced farms covering every available piece of land

View from our car - the road can be very narrow

At least you get to see Truck art details up close

Rakaposhi Viewpoint Cafe

My souvenir purchase - a traditional hat from Hunza - hand embroidered on cloth. Women wear them with a scarf over the top

Rakaposhi Viewpoint Cafe

Rakaposhi

A final road stop before continuing on to Hunza

My favourite view of Rakaposhi, terraced farms, flags flying in the wind

Postcard from the Kargah Buddha

The layers of history in Gilgit-Baltistan are fascinating. The area began as a number of small, independent states but the region has had many rulers and religious influences, from Chinese, Tibetan, to Mughal, from Buddhism to Islam. All have left lasting influences on art, culture, language and architecture.

Gilgit was an important trading stop on the Silk Road. Buddhist monks from China followed the Silk Road and it became a corridor for the teaching of Buddhism across the region. From the 3rd to the 11th century Gilgit was a major centre for Buddhism and many monasteries and stupas were built.

In 1931 a monastery and three stupas were found along with a large number of manuscripts that can be dated back to the 6th and 7th centuries. The archaeologist Aurel Stein announced the discovery of the manuscripts. They are made from birch bark and because of the dry mountain air they are in a remarkably good condition. In fact, they are the oldest surviving manuscripts in India. They cover a wide range of subjects including religion, folk tales and medicine. Most of the Gilgit manuscripts are in the Indian National Archives while a small number are in the British Library and the Karachi Museum.

Why am I telling you about the manuscripts? The manuscripts included a lot of new information on the region. Aurel Stein continued to make expeditions through the area reporting on findings of monuments and rock carvings. We had come to visit the largest rock carving, the Kargah Buddha.

Archeologists believe that the Kargah Buddha carving was completed in the 7th century. The Buddha can be found high up on the Kargah Nala cliff-face. The Buddha is 15m high and looks out over the Kargah and Shukogah Rivers that flow down to meet the Gilgit River.

There is also a legend about the carved figure, known locally as Yshani. Yshani was a man-eating giantess who terrorized the area. A holy man managed to pin the giantess to the cliff. The holy man declared that she would no longer bother them as long as he was alive. It is said that the holy man is buried in the foothills and so now the giantess can never be freed.

Now that we don’t have to worry about a man-eating giantess the area is a lovely picnic spot. Recent renovations have improved the road up to the Buddha and new stairs make it easy to climb up to get a great view of both the Buddha and the valley below.

View of the Buddha from across the valley

The new road that leads up to the Buddha

There is a small bridge to cross and an easy walk to the bottom of the stairs

The walkway takes you past rushing water

Edge of an old mill

The water was used to power the mill that still works today

The start of a steep walk

Stop, catch your breath, admire the view

Steep but stable stairs

The valley quickly becomes very narrow

Closest view. The holes around the Buddha were believed to be for a wooden structure to protect the carving. Or for pinning down a man-eating giantess!

Postcard from Gilgit

Gilgit-Baltistan covers an area of over 70,000 square kilometres and has an estimated population of nearly 2 million with over 200,000 people living in Gilgit, the capital of the territory. It is bordered by Afghanistan, China, Pakistan Administered Kashmir and Indian Administered Kashmir. Gilgit-Baltistan is an administered territory of Pakistan and constitutes the northern portion of the larger Kashmir region. Kashmir has been subject of a dispute between India and Pakistan since 1947.

To say that the region is mountainous is a massive understatement. It is home to three mountain ranges: Hindu Kush, Karakoram, and the Himalayas. It has five mountains above 8,000 metres: K2 (8611m, Karakoram, just behind Everest at 8850m); Nanga Parbat (8126m, Himalayas); Gasherbrum I (8068m, Karakoram); Broad Peak (8047m, Karakoram); Gasherbrum II (8035m, Karakoram). It also has more than fifty mountains above 7,000 metres.

The airport in Gilgit is surrounded by mountains and the approach is difficult. Poor weather or high winds mean many flights are cancelled. We are lucky as our flight from Islamabad to Gilgit leaves and takes just over an hour. I’m glad the weather is favourable as we seem to skim over mountain ranges as we fly north and the approach into Gilgit seems to be very close to the side of a mountain. I am also glad that we are not driving to Gilgit as the drive would take around sixteen hours due to poor roads.

We spend the afternoon looking around Gilgit. The bazaar is quiet as we are travelling during Ramadan. It is watermelon season and everywhere we go we find large barrows with neatly stacked melons, some cut to show off the ruby red inside. There are many shops and stalls selling dried fruit as the area is famous for walnuts and apricots. We visit two suspension bridges, one for cars and one for pedestrians. I’m not sure I would be brave enough to drive a car across the bridge as it is very narrow, the wood creaks and the bridge sways from side to side and up and down. Even with the swaying I manage to take many photos of Gilgit and the river.

Flying from Islamabad to Gilgit

The mountain ranges disappear into the distance

Flying into Gilgit

As you approach the airport you fly very close to the mountains on the left hand side of this photo

The small but welcoming Gilgit Airport

View of Gilgit from the Serena Hotel

Car suspension bridge

Gilgit River

Gilgit River

Just enough room for cars and pedestrians

Orange tarpaulins cover livestock

Pedestrian suspension bridge

The end of the pedestrian suspension bridge and the start of the bazaar

Gilgit Bazaar

Gilgit Bazaar

Selling jalebis (orange swirls - batter is fried and soaked in a sugar syrup) and samosas

Naan seller

Watermelon season

Traditional topi (hats), tasbih (prayer beads) and perfume

A thumbs up from a local

Another friendly local wandering along the Main Street

Dried fruit and nut seller

Life in Islamabad Eid-ul-Fitr

Box of traditional Pakistani sweets

Eid-ul-Fitr

Eid-ul-Fitr is the first day of the Islamic month of Shawwal. It marks the end of Ramadan, the month of fasting and prayer. Shawwal begins, and Ramadan ends, after a confirmed sighting of the new moon.

At Eid-ul-Fitr there are communal prayers and the giving of ‘zaka al-fitr’ or charity. It is also a festive time, to visit family and friends, give presents, to buy new clothes and prepare special meals.

Eid-ul-Fitr is also known as ‘Meethi Eid’ or sweet Eid in Pakistan. Celebrations have to include sweets. Traditional desserts are made like Sawaiyan and gift baskets of sweets are sent to friends and family.

There are two types of Sawaiyan – Sheer Khurma and Kimami Sawaiyan. Sheer Khurma is a milk pudding made with special vermicelli noodles that are cooked in thickened milk. Dates, fried lotus seeds, raisins, nuts and spices such as ‘elaichi’ or green cardamom are added to the milk. I have added a recipe for you to try.

To all who are celebrating, I want to wish you ‘Eid Mubarak’, a blessed Eid.

Sheer Khurma Recipe

Ingredients:

· Milk – 1 litre

· sweetened condensed milk – 200g

· Ghee – 2 tbsp

· Dates – 10 (dry)

· Green Cardamon pods – 3 – slightly crushed

· Vermicelli – I cup

· Sugar – ¼ cup

· Saffron – 1 pinch

· Nuts – ½ cup (you can use a mix and you can chop and/or keep whole)

· Raisins – ½ cup

Method:

1. Soak dates in warm water overnight. Remove seeds and chop finely.

2. Boil the dates in 1 cup of milk, the dates will absorb all the milk and become very soft.

3. Take 1 tbsp of milk and add the saffron threads.

4. Take the remaining milk and bring to a boil, reduce heat and cook and keep stirring for around 30 minutes or until thickened. Add the condensed milk.

5. In a separate pan add the ghee, cardamom and vermicelli and cook until a light golden brown.

6. Add the cooked vermicelli mix to the milk and cook for a further 10 minutes.

7. Add additional sugar to taste and cook until dissolved.

8. Add the saffron milk, half the dried fruit and softened dates. Stir to combine.

9. Garnish with remaining dried fruit and dates. Serve warm or cold.

Sheer Khurma

A gift basket we received with wonderful treats

My favourite sweet - Multani Sohan Halwa. See my blog on this traditional and delicious sweet.

Almond biscuits called Khatai - wonderful with chai

Another favourite of mine, Revri, made from sesame seeds.

Barfi, with silver leaf to make them extra special

Covered in sesame seeds and fried - yum!

Motichoor ke ladoo - made with almonds, ghee and sugar

All sorts of different pastries are also given as gifts.

Postcard from Multan’s Walled City and Historic Gates

Haram Gate

Multan was once a fortified city with a wall and six gates. What remains of the wall is now in the inner part of the city centre. Entrance to the walled city was by six, imposing gates: Lohari; Bohar; Pak; Dehli; Haram and Dolat. Only three gates remain: Dehli; Bohar and Haram. The original wall and gates were built in 1756 however during the British siege of Multan in 1849 much was destroyed. The British rebuilt the Dehli Gate and some restoration work on the other gates has occurred.

The remaining gates all have interesting histories. The Dehli Gate was the gate that Mughal kings would enter the city. The gate faces Dehli, India. Bohar Gate faced the Ravi River that had Bohar trees along its banks. Food and supplies would be brought along the river and enter the city via this gate. The river has now changed course. Haram Gate was next to the women’s quarter, or harem, of Saint Musa Pak Shaheed.

Shops and people crowd up against the remaining parts of the wall and gates. Inside the walled city are narrow streets with some wooden houses with intricately carved doors, windows and balconies. There was no time on this trip to explore the old town, yet another reason to return.

Haram Gate

Dehli Gate

Dehli Gate

Bohar Gate

Part of the old wall

Old wall and carrot juice

Old wall and wedding carriage

Old wall and donkey

Multani Kaashigari

After travelling to many parts of Multan, Bahawalpur and the Cholistan Desert and seeing the beautiful Multani blue and white glazed tiles I was interested in learning more about this art. The blue and white pottery is known locally as Kaashigari.

The word Kaashigari is thought to have come from either Kashan in Persia or Kashgar in China. There are certainly Persian influences in the designs and Chinese influences in the predominant use of blue and white. The art form has developed with unique Multan designs and overtime the number of colours used has increased to include bright red, yellow and orange.

Kaashigari used to combine both red and white clay from local riverbeds however water pollution has meant a change to using just white clay from different parts of Pakistan. Added to the clay is feldspar and quartz. Kilns have replaced wood and dung fires.

We visited both the TEVTA (Technical Education and Vocational Training Authority) Institute of Blue Pottery Development, a government run institute, and the Ustad Alam Institute of Blue Pottery. The TEVTA Institute runs a 6 month course and trains around 40 students a year. The TEVTA institute trains both men and women, women mainly working from home. We were also given a tour of the Ustad Alam Institute of Blue Pottery. The Institute is run by Ustad Muhammad Alam, an acclaimed Pakistani artist who has won numerous awards.

It was fascinating to see the process from start to finish. The mixing of the clay, clay being poured into moulds, the hand painting through to glazing and firing. At both institutes I was able to watch the artists painting directly on to the pots with no outline or pattern to follow. The rooms were quiet, light coming through side windows, their brushes moving quickly, no mistakes made.

And yes, I bought a lot of pottery to bring home with me…….

Clay

Barrels for mixing the clay

Long wooden shelves with iItems waiting to be painted

After the item comes out of the mould the excess clay is trimmed away

Kiln

Preparation of a mould

Metal mould supports

Mould being filled with clay

Glaze being mixed

Hand dipping items into the glaze

Postcard from Abbasi Royal Graveyard

Our final stop for the day was the Abbasi Royal Graveyard. It was a short but dusty drive to the graveyard where we waited for the caretaker to come and open the gate. A large key was extracted from a pocket of the caretaker’s shalwar kemeez and the door was slowly opened. There are several tombs here, individual tombs for wives and relatives and the main Nawab tomb. The Nawab tomb contains the graves of all 12 Nawabs that ruled Bahawalpur. The outside is red brick with traditional Multani blue and white glazed tiles. Inside the tomb you can see the individual tombs respectfully covered in white cloth. The interior is highly decorated with frescoes, elaborate wood doors and tile and mirror work. We started our visit to the Cholistan Desert with the fort and man’s attempt to control his environment, we then visited the mosque and contemplated life today and ended at the graveyard and a reminder that one day we will all return to dust.

Postcard from Abbasi Mosque, Cholistan Desert

From the top of one of the bastions of Derawar Fort you can see the Mosque’s three white domes shining through the afternoon haze. The Mosque was built in 1849 by Nawab Bahawal Khan Abbasi. Covered in white marble the mosque is symmetrical with minarets and decorative arches and Islamic calligraphy. The design was supposed to have been inspired by either the Shah Jahan’s Moti (Pearl) Mosque in Agra or the Moti Mosque at the Red Fort in Dehli.

We had time for a quick stop to see the mosque before continuing our journey. We took off our shoes and I covered my head. Inside the courtyard it was hot in the afternoon sun and very quiet. Time for a moment of quiet contemplation.

Postcard from Derawar Fort, Cholistan Desert - a fortress of truly towering proportions

We leave Bahawalpur behind and travel another 100 kilometres into the Cholistan Desert. Derawar Fort rises up out of the desert and the colour of the surrounding sand is matched by the millions of small, narrow bricks that make up the fort.

40 bastions standing 30 metres tall, 1500 metres of wall make up the square shape of the fort. Each bastion is decorated with intricate brick work patterns. As you get closer you can’t believe the scale of the building, seemingly built in the middle of nowhere.

When the Fort was built in the 9th century it stood next to the Hakra River and was a defensive point to protect valuable water resources on caravan and pilgrim routes across the desert. It was built for Rai Jajja Bhati, a Hindu king from Jaisalmer, India. The fort changed hands many times and in the 18th century it became the property of the Nawabs of Bahawalpur, who rebuilt it in 1732.

Inside the Fort are many buildings, most in a poor state of repair. The Bahawalpur Department of Archaeology is working to restore parts of the fort but more work and funds are required. We visited one bastion where the structure has been repaired and new frescoes painted but it is a shame that the original frescoes are not protected.

The fort is currently on the tentative list of sites to be included on the UNESCO World Heritage List. UNESCO defines cultural and natural heritages as “irreplaceable sources of life and inspiration…our touchstones, our points of reference, our identity”. Derawar Fort certainly meets that definition.

Gateway into the fort

Curved, steep driveway from main gate - excellent defences

Panorama inside the fort

Bastion currently under restoration

Walkway up to see the bastion restoration work - no railing, long drop down - don’t think I’d like to work on the scaffolding

Restoration inside almost complete

Ceiling detail

Frescoes - before and after

Wall detail

View from the bastion - where the irrigation stops the desert immediately starts

Inside the fort - years of restoration work required

Inside the fort

Inside the fort

Under the dust a hidden treasure

Parts of the buildings look beyond repair

Painted ceiling

Bastion brickwork

Time to leave to go to our next stop - decided against the camel to get there

Cars are a much better option against the heat and dust

Postcard from Sadiq Garh Palace, Bahawalpur - neglected but not forgotten

After visiting the centre of Bahawalpur, we took a small detour to visit Sadiq Garh Palace. We were just going to stop and have a look on the outside before continuing on to see Derawar Fort. But one wrong turn into a private driveway led us to meeting the Nawab and his family and an invitation to visit inside the Palace and to stay for tea. I am constantly amazed at how generous and hospitable Pakistanis are to people they don’t know.

The Palace was built for Nawab Sadiq Muhammad Khan (IV) in 1882 and took ten years to build. Italian architects designed the building that has both European and South Asian influences. The Palace has three floors and sits in a large, symmetrical garden with a mosque to one side.

The Palace has been left empty now for years. Glass is broken in the ornate windows, tiles are missing, wooden floors are rotting away. There is little left of the interior furnishings, three ornate mirrors remain in a downstairs room, too heavy to move or steal.

Apparently there are a large number of heirs to the property and there is no agreement over what to do with the Palace. Suggestions include keeping it in the family, handing it over to the local Government to turn into a museum or selling it to become an hotel.

It is a beautiful building and we can only hope a decision is made soon before the building is beyond restoration and we lose a valuable part of Bahawalpur’s history.

The family Mosque

Postcard from Bahawalpur Central Library

We visited the Bahawalpur Central Library and my knowledge on architectural styles was broadened again. The Library was built during the British Raj and you can easily see the Victorian influence. It is built in a Neo-Gothic-Victorian style, also known as Gothic Revival. The library includes all the major decorative items such as moulded frames for windows, arches and lancet windows (tall with a pointed arch at the top).

Construction started in 1927 but took seven years to finish due to lack of funds. I was given a wonderful tour of the library including the rare book section and the library’s amazing collection of early editions of both Dawn and the Pakistan Times, two Pakistani newspapers established by Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan. I could have spent a lot of time sitting and reading through the newspapers. I opened the Pakistan Times on Saturday April 26, 1947. One headline was “Viceroy determined to play fair on Frontier issue”. The Viceroy was Lord Mountbatten.

The central reading room is beautifully proportioned with light streaming in. The top gallery has an Islamic art collection. Next to the main library is the Children and Ladies Section that includes a room of braille books. In the children’s section there was a large book on major cities around the world. The book was opened to Sydney in honour of our visit. Nice to think that the next day someone might sit and read about Sydney, Australia, while living in Bahawalpur, Pakistan.

Central reading room

Illuminated Quran

Radha is a Hindu goddess and consort of the god Krishna

I love old catalogue card cabinets

Pakistan Times, Saturday April 26, 1947

Gallery

Braille book

Children’s library

Seeing the Opera House made me feel a little homesick

Main entrance to the library

Postcard from Noor Mahal, Palace of Light, Bahawalpur

If you visit Multan, then a day trip to Bahawalpur is a must.

Bahawalpur was formerly a princely state, ruled by the Abbasi family until 1955. Bahawalpur was founded in 1727 by Nawab Sadiq Muhammad Khan Abbasi. Nawab is a royal title, comparable to a prince. On 22 February 1833, Abbasi formed an alliance with the British and so Bahawalpur become a princely state of British India. When India became independent in 1947 Bahawalpur joined Pakistan and in 1955 it became a province of Pakistan.

We started our day with a visit to Noor Mahal, also known as the Palace of Light. The palace was built in 1872 and incorporates many different styles from Greek to Italian to Islamic. The building was designed by a British engineer, Mr Heenan, for Nawab Abbasi IV for his wife. It is believed that his wife only stayed there for one night as she didn’t like that she could see a graveyard close by.

In 1956, after Bahawalpur become a province, the palace was administered by a department of the local Punjab Government. The building had fallen into disrepair and many items had been stolen. In 1971 the palace was leased to the army. In 1997 the army purchased it and restored the building. It is now a protected monument and open to the public.

While the building has been beautifully restored and contains many antiques, including a 1935 Ford Caravan that the Nawab used for Hajj, my favourite part of the tour was the gallery of historic photographs. It makes me wonder if someone will look at my photographs one hundred years from now and wonder about the people and what their lives were really like.

Front entrance hall

Ceiling and chandelier

Intricate tile work

One exhibit in the small museum

1935 Ford car and caravan

Inside the caravan

Postcard from Shah Shams Sabzwari Shrine - a saint, a shrine, a story

We visited Multan in March as the weather was good for travelling, it was considered mild with most days in the low 30 degrees Celsius. Multan experiences some of the most extreme temperatures in the country with very cold winters and long, scorching summers. As Multan sits close to the Cholistan Desert the city also experiences many dust storms. The average temperature in summer sits in the mid 40’s but it has reached into the mid 50’s.

The air had cleared the day we visited the Shah Shams Sabzwari Shrine to reveal a light blue sky with white clouds. The shrine was the least well looked after shrine we visited in Multan. Built in 1329, extensively damaged by fire in 1770 and rebuilt in 1779. It once sat by the side of the Ravi River, but the river has now moved. I am now beginning to recognise the Multani style of architecture for shrines – a square base, topped by an octagonal level, minarets on each corner, finished with a dome, this time the dome was green not white. There were, of course, lots of beautiful Multani glazed tiles. Across the courtyard from the shrine sits a white mosque. Inside and outside of the shrine it is busy with people and stalls selling religious items, souvenirs and traditional Multani wood blocked print cloth.

When I was doing some background reading for this blog, I found a wonderful website called Oriental Architecture (link below). As well as the usual information on building dates and dimensions I came across the most wonderful story about Shah Shams Sabzwari and Bahauddin Zakariya (see my previous blog on his shrine).

The story goes that when Shams arrived Zakariya was not happy as he didn’t like yet another saint arriving in his city. Zakariya sent Shams a cup filled to the top with milk. A not too subtle way of saying the city is full of saints. Shams sent the full cup back with a rose petal on the top as a way of saying his presence wouldn’t disturb Zakariya.

Zakariya wasn’t happy about the cup being returned so ordered the city merchants not to sell anything to Shams. Shams took pity on his disciples who were hungry and caught a pigeon for them to eat (you will have seen from my other blogs how important pigeons are in the city and that there are so many of them). But no merchant would agree to cook the pigeon. Shams took the pigeon and asked the sun to come closer and cook the bird. The sun came closer, the bird was cooked. The sun never moved back to its original position and this explains why Multan is so very hot.

I want to return to Multan to seek out more of its wonderful treasures, but I won’t return in the summer!

https://orientalarchitecture.com/sid/1321/pakistan/multan/shah-shams-sabzwari-tomb

Entrance to the courtyard surrounding the shrine

green dome, blue tiles, red bricks

Entrance to the shrine

Multani blue and white glazed tiles

Ceiling detail

Multani blue and white glazed tiles

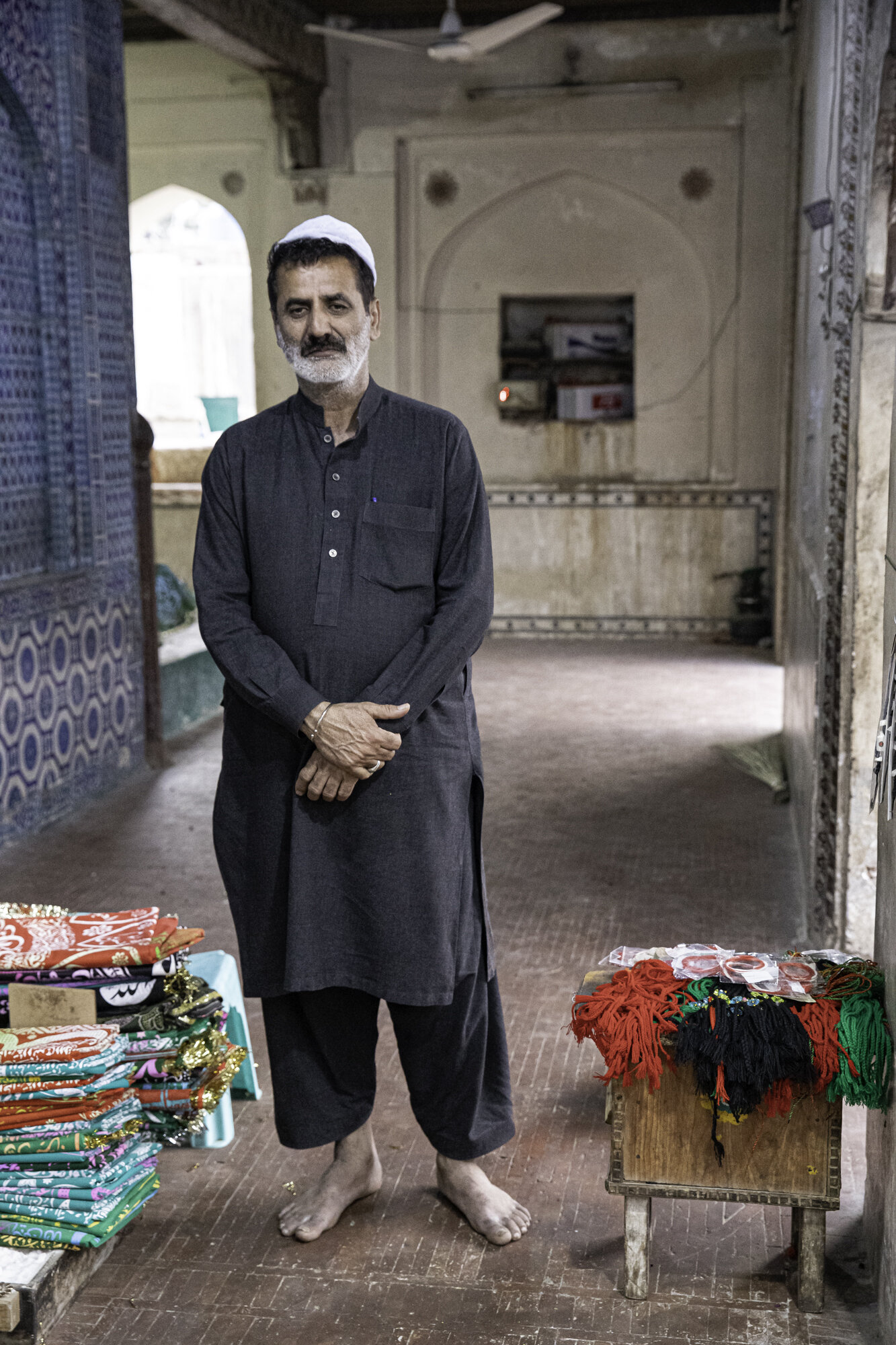

Man selling religious items

The mosque inside the courtyard

One of the entrances to the mosque