Postcards from Pakistan

Portrait of Humanity

For the last five years the British Journal of Photography has put together a book called the ‘Portrait of Humanity’ to ‘recognise remarkable portraits that capture the moments that make us who we are’. Volume 5 includes 200 images from across the world.

The book provides ‘a window into the lives of the subjects and celebrates the shared humanity that connects us all’. I am so excited to share that one of my portraits was chosen for the book. I was so fortunate to travel throughout Pakistan and to visit remote areas of Gilgit-Baltistan. The people we met and the hospitality we received will forever stay with me.

Follow the link below to see all 200 images. You can also purchase the book from Hoxton Mini Press.

https://www.1854.photography/2023/02/portrait-of-humanity-vol-5-shortlist-revealed/

Postcard from Skardu - one day, two lakes

Upper Kachura Lake

Sadly our time in Gilgit-Baltistan is coming to an end. We have one full day left in Skardu before flying back to Islamabad. Skardu is a city surrounded by mountains sitting next to a wide valley floor at an elevation of 2,500 metres. In the local language of Balti Skardu means ‘a low land between two high places’. I was also told it could mean ‘star stone’ or ‘meteorite’. The landscape is dramatic as the Indus and Shigar Rivers meet here. The rivers keep changing shape as erosion from the Karakoram Mountains has left large deposits of sediment in the valley. We drive through the busy city and get caught in traffic jams caused by cars, people, and cows.

We are staying at the Shangrila Resort built around Lower Kachura Lake. When the sun hits the lake it is a bright green in colour. Upper and Lower Kachura Lakes sit side by side. We drive closer to Upper Kachura Lake and take the short walk down to the water’s edge. Boats sit ready to take visitors out on the lake, but we decide to enjoy the peace and quiet and sit and enjoy the wonderful view. On our way back to the car the path is filled with goats returning from grazing. We quickly move over and stand on a low wall and watch as they wander past.

The sun is beginning to set as we head back to the Shangrila Resort. We stop and buy some local dried fruit: cherries; sultanas; apricots; and walnuts. We sit outside our cabin and eat some dried cherries and start planning our return to this beautiful part of Pakistan.

Skardu Valley

Skardu City

Lower Kachura Lake, Shangrila Resort

Boating on Lower Kachura Lake

Lower Kachura Lake

Path on way to Upper Kachura Lake

Upper Kachura Lake

Flag with the face of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, known as the ‘Father of the Nation’

Flying out of Skardu

In the clouds, dreaming of our next visit north

Postcard from Hushe Valley and Masherbrum, Queen of Mountains

I had never heard of the Hushe Valley in Gilgit-Baltistan. However, it is well known to the trekking and mountaineering community. Hushe Village sits at the very end of the Hushe Valley. Sitting behind the village is Masherbrum at 7821m. There is a well-known K2 base camp trek that starts at Askoli Village, trekking across the Baltaro Glacier, Concordia, finally crossing the Gondogoro Pass before arriving in Hushe Village.

We were not doing the trek. Instead, we were driving to Hushe Village from Khaplu. It is a 60 kilometre drive and you need to allow around 3 hours as the roads after Saling are single lane and most of the road is not paved. The Hushe River runs down the valley eventually meeting up with the Shyok River.

We left Khaplu and crossed the Shyok River at Saling. We stopped to take photos at Saling of the Ghursay Mountains. Ghursay is the local name for K7 (6934m), K8 (7422m) and K9 (7000m). There are many villages to stop and walk around along the way: Machlu; Talis; and Khand. As we wanted to reach Hushe and get back to Khaplu before dark we only stopped a couple of times to take photos. This turned out to be a good idea as on our return our car broke down. Somewhere along the very bumpy road we had lost a vital connector. Our wonderful driver, Shakeel, walked along the road, found a suitable piece of plastic and tied the parts together and we were able to get back to Khaplu.

Our tour guide had organised for a local man to give us a tour of Hushe. Hushe is predominantly a farming community. In the 1960s villagers started working as porters and cooks for K2 expeditions. Expeditions brought work and money to this very remote community. However, covid has meant that the number of expeditions has significantly decreased. There is a primary and middle school, any further education must take place in Skardu, over 5 hours away. The cost is prohibitive for many families. The other major challenge for the village is water. There is only one water pump and this freezes over winter.

We stopped and talked to several people as we walked around the village. One woman was happy for me to take her photo but was insistent I do not post to Facebook. I was surprised that Facebook had made its presence felt in such a remote place. A grandmother was minding her grandchild and was very happy for her photo to be taken. The grandchild was not and cried and cried! As a mother and daughter sifted tea leaves, we were told of the process of growing and making the local green tea. A couple of cows became very interested in us and a small boy was dispatched to drive them away. We visited in late April and, at this end of the valley, it was still looking barren as this is the start of the planting season. Men and women were working together in the fields surrounding the village getting the soil ready. Villagers rely on these crops and the growing season is extremely short.

Wherever you walk in the village you feel the presence of the mountains and Masherbrum. Brum means mountain in the local Balti language. Many meanings have been given for Masher from ‘queen’ to ‘no sunlight’. If K2 is the ‘King of Mountains’ in Pakistan, then perhaps Masherbrum is the Queen.

Ghursay Mountains (K7 (6934m), K8 (7422m) and K9 (7000m))

Machlu Village

Machlu Village

Fields outside Machlu Village

Extra rocky part of the road

Apricot trees are left to soak in the mountain streams before planting

Spring seems a long way off

IFAD Project - apricot orchard

Looking back towards Saling

Hushe Village

I was very sorry that I made this poor child cry

Sifting green tea

Curious cows

Tin cans used to make a very useful gate

Education for all

Enter to read….leave to lead

Education is the best tool to change the world - Nelson Mandela

Education is the process to produce a sound mind in a sound body - Aristotle

Refugio Hotel - a gift from the Spanish Government

Postcard from Thoqsikhar Mosque - a steep climb for the best green tea

We are staying in Khaplu that is in the Ghanche district, the easternmost district of Gilgit-Baltistan. To the north is China, to the south is Kashmir. I love hearing these beautiful sounding place names, even before arriving it sounded like a magical, exotic place.

If you visit this area of Pakistan you must bring your hiking boots with you as the best views can only be seen on foot. So we pulled on our hiking boots and set out to visit Thoqsikhar Mosque that sits high above the Khaplu Valley.

It is difficult to find any information in English about this five hundred year old mosque that sits at over 2,700 meters, high above the Khaplu Valley. The mosque is also known as Thoksikhar, Thoqsi Khar, or Thoksi Ghar. We drove to Gharbuchang Village to start the walk. Our guide, Mehrab, told us that it was a gentle walk and should take around 45 minutes to reach the top. The walk through the village was gentle, as was the first five minutes around the fields. Children peeked out from behind gates and a little goat followed us until a cow looked like more fun to play with. However the next 40 minutes of the walk was steep. It was hard work walking at altitude. I kept stopping to take photographs but it also gave me an opportunity to catch my breath.

Up and up we climbed. The views of the village and the valley kept getting better and better. Close to the mosque we were met by two local men who offered us tea and a place to sit and rest. We decided to keep going and stop on the way back. We finally reached the mosque and were able to enter and walk around the outside terrace. Past the mosque there is a short walk to reach the lookout where you get spectacular views of the Khaplu Valley. We enjoyed the cooling breeze, took more photos and then turned around to head back down before the sun set. At a small terrace a local, green tea was ready and waiting for us. We sat and enjoyed the tea and the view – both were wonderful.

Thoqsikhar Mosque sitting high above the Khaplu Valley

Gharbuchang Village

Gharbuchang Village

Gharbuchang Village

Looking back across the valley at Gharbuchang Village

Getting closer to the mosque

Gharbuchang Village and Thoqsikhar Mosque

Mehrab places a stone to celebrate that we made it this far.

Stopping to catch my breath

Thoqsikhar Mosque

Thoqsikhar Mosque

Entry to the terrace that surrounds the mosque

Inside the mosque

The lookout

Khaplu Valley

Down in the valley below we can see Khaplu Fort

Excellent maker of green tea

The tea, the view.

Postcard from Khaplu Village and Valley - a green, pink and turquoise walk

Khaplu is famous for its beautiful scenery and for being the gateway to trekking and mountaineering. It is also known for Khaplu Fort (see my separate blog on the Fort) and for Chaqchan Mosque. We wanted to understand the area better so we took a walk around Khaplu Village and then walked up the mountain behind the Fort to get a better view of Khaplu Valley.

The village was busy with women washing clothes and children running along the dusty paths hitting metal hoops to see how far they would roll. Men were sitting in front of their shops chatting with each other.

As we walked past local houses we saw what looked like a noughts and crosses game written on the walls or doors but instead of the usual noughts and crosses the grid was filled with a jumble of letters and numbers. I asked what it meant and was told it was a way of keeping track of immunisation and census records for that house. Written records, including a vaccination card for each child, are kept but the wall markings make sure no child is left out of a vaccination drive.

We were hoping to see inside Chaqchan Mosque. However, a sign outside stated ‘no admission for non-Muslims’. I was disappointed as I had read a lot about the Mosque that was built in 1370 and is one of the oldest in the region. Chaqchan means ‘Miraculous Mosque’ maybe one day we can return to see why.

We kept walking along a track that starts at the polo field and climbs up the mountain. The walk is steep but wonderful as you get amazing views of the village and the valley. At the top we kept walking along the main road until we reached rocky orchards and fields, all surrounded by mountains. We stopped and sat on a stone wall and enjoyed a well-earned rest. As we looked over green fields, pink blossoms, snow-capped mountains, and a turquoise blue farmhouse it was easy to agree that Khaplu is a beautiful place to visit.

Khaplu Village - each house a different colour

I always ask if I can take someone’s photo. This lead to a long discussion and the group decision was this man was the most photogenic.

Immunisation records on door

Chaqchan Mosque

The edge of the track up the mountain

Khaplu Valley - the view was worth the walk from the village below

A wonderful place to sit

Postcard from Khaplu Fort - where the stone stopped rolling

During our drive across Gilgit Baltistan we’ve been able to see some amazing forts: Baltit and Altit Forts in Hunza; Shigar Fort and now Khaplu Fort (see my other blogs on each of the forts).

Khaplu Fort, like the other forts in the region, has been restored by the Aga Khan Cultural Service Pakistan. This fort is yet another example of painstaking restoration. The fort is set in Khaplu Village near the banks of the Shyok River and is surrounded by fields and orchards. In the village you can stand and turn and have 360 degree mountain views. You can see Masherbrum, K-6, and K-7 and other mountains with beautiful names like Sherpi Kangh, Siachen and Saltoro Kangri.

The local name for Khaplu Fort is Yabgo Khar, also known as ‘The Fort on the Roof’. The local story is that a stone was rolled down from a nearby mountain and where the stone stopped they built the fort. Built in the 1840’s for the local ruler Yabgo Raja Daulat Ali Kahn, it replaced an older fort. The fort showcases the many different styles of the region: Tibetan; Balti; and Kashmiri.

Today the Fort is run by Serena Hotels. We stayed for three nights to explore the region. We had a wonderful stay there. What an experience to drink tea on an intricately carved wooden balcony and to sit on the top terrace and watch the moon rise over the mountains. Khaplu Fort, where the stone stopped rolling, and, if you can, you should stop there too.

Main Gate

Entrance to Khaplu Fort

Khaplu Fort garden

Khaplu Fort restaurant

A lovely place to sit and enjoy a meal

Wooden lattice work

Doors open to a spectacular balcony and view

We sit and enjoy our tea

Ceiling detail

Door detail

Everywhere you look there are interesting details and objects. These boots a reminder that the sun doesn’t always shine here.

Ceiling detail

Our favourite breakfast spot

A little cool in the mornings but we had to sit outside as it was such a gorgeous view

Night falls

A romantic dinner for two was organised and we sat and watched the moon rise

Postcard from Keris - the door to heaven

We say a fond farewell to Shigar and get ready to drive the two hours, 104 kilometres, to Khaplu where we will be staying for the next few days.

The two-hour drive takes us close to four hours as I want to stop so many times to take photographs. The scenery continues to be stunning but the road is not. The road is only paved in parts and the rest was very bumpy, so much so that my Fitbit congratulated me on doing my daily target of 10,000 steps.

My favourite stop was at the Keris pedestrian bridge, suspended over the Shyok River. We walked across the bridge in the bright sunshine. It was obviously a good day to do washing as many women were by the river’s edge washing clothes in the icy river and draping them over hot stones to dry. Keris is at the confluence of the Indus and Shyok Rivers. As you sit and look at the bridge and the turquoise river, your eyes move up past the beginning of the green valley to snow capped mountains. You can see why the bridge has been called ‘the door to heaven’.

Leaving the green Shigar Valley

Under all that hay is a house. Limited land means using every available surface for drying.

Gol Village in the Indus River

Stopping at Keris

Keris pedestrian suspension bridge

The green-blue bend of the Shyok River

Keris road suspension bridge in the background

Ghawari

Postcard from the Manthal Buddha - a rock and a desert

The Manthal Buddha can be found just outside the village of Manthal, near Sadpara Lake. Buddhism came to the region in the late 7th century. Buddhists travelled throughout the Indus Valley, and you can see rock carvings and stupas across Gilgit-Baltistan. Two of the most famous sites are the Manthal Buddha and the Kargah Buddha (the subject of a previous blog).

The Manthal Buddha was carved in the 9th century, during the ‘golden age of Buddhism’ in the region. The rock is in the shape of a triangle and is approximately 6 meters wide and 9 meters high. The carving on the rock shows a meditating Buddha surrounded by smaller Bodhisattvas (past buddhas) and two standing Maitreyas (future buddhas). At the bottom of the rock are some Balti inscriptions. The carving is a Mandala, a representation of the universe and an aid to meditation. The local village Manthal is named after the carving.

The Buddha Rock is surrounded by a wall and there is a custodian. I was pleased to see that the local government has taken steps to preserve and protect the site. Some Buddhist sites have been vandalised in Pakistan as they are considered to be un-Islamic.

On the way back to Shigar we stopped to look at the Sarfaranga Desert, known as a cold desert, during the winter it can be covered with snow. The landscape is dry and dramatic. Desert surrounded by mountains. We visited in late spring, and you could feel the warm wind crossing the sand. It is hard to imagine that snow could fall here. Maybe one day I can return to photograph what would be an amazing sight of a desert covered in snow.

Manthal Buddha and custodian

Sarfaranga Desert, mountains to the front and back

Sarfaranga Desert

Sarfaranga Desert

Postcard from Sadpara Village - a tribute to Ali Sadpara

‘In climbing there are two outcomes, life or death, and you must find the courage to accept either possibility’. Muhammad Ali Sadpara

We had planned a day trip to Deosai National Park but multiple rockslides on the road meant we had to turn back to Shigar. The change in plans gave us the opportunity to spend more time at places of interest along the way.

We stopped first to look down at Sadpara Village, also known as Satpara. From the road you look across the valley. Colourful houses gathered closely together surrounded by terraced fields. We stood and appreciated the work involved in creating neat rectangles of fields, some bright green, some recently tilled, edged by stone walls. As the valley walls become steeper the fields become narrower and the walls higher. Water channels provide irrigation from streams to the fields.

It was in Sadpara Village that Muhammad Ali Sadpara was born in February 1976. It is easy to see when standing in his village, surrounded by mountains, why Ali Sadpara became a mountaineer. He started as a porter, carrying heavy loads for expeditions to the Boltoro Glacier and K2, then progressed to leading expeditions. His mountaineering achievements are numerous and include climbing eight of the fourteen ‘eight-thousanders’.

In November 2020 we were lucky enough to meet Ali and hear him give a talk about his climbing life. He was quietly spoken and modest about his achievements. It was only when you see some of the video footage from his climbs that you realise what an amazing but dangerous occupation Ali had chosen.

In January and February of 2021 Ali and his son Sajid planned another expedition to K2 along with the Icelandic mountaineer John Snorri and Chilean mountaineer Juan Pablo Mohr. On 4 February Sajid returned from the highest camp due to equipment problems while the other three pushed on to the summit of K2. They failed to return and despite rescue missions have not been found. The whole of Pakistan mourned the loss of its most successful mountaineer and a family their dear husband and father.

"To all the climbers... who look up to him. I promise I will carry on his dreams and mission and continue to walk in his footsteps." Sajid Sadpara

Postscript: It has been reported in the media today that the bodies of Ali Sadpara, John Snorri and Juan Pablo Mohr have been found just above the area known as the Bottleneck on K2. May you all now rest in peace.

Road to Deosai, whole parts of the road ripped away

I’m not sure why I am smiling as these huge boulders blocked our way to Deosai.

Sadpara Village on the far right, tucked in close to the mountain side

Sadpara Lake in the distance

We round a corner and there is this beautiful bridge

Our wonderful guide Mehrab willing to climb out on a rock so that I can get a great shot

A less adventurous photo

Ali Sadpara, event hosted by the Canadian High Commission, November 2020

Sadpara Lake

Postcard from Shigar - one village, two historic mosques

Khilingrong Mosque

Before travelling to Shigar I had read about the Shigar Fort. What I hadn’t read about were the two historic mosques, Khilingrong and Amburiq.

As we walked around Khilingrong Mosque, built over 400 years ago, we admired the unusual design. It has two stories, the lower story used during winter and the upper story used in summer to take advantage of any breeze. While the verandah on both levels is made from intricately carved wood, the inside is made from the traditional method of building alternate levels of wood and stone. Instead of four minarets there is a central tower that is Tibetan in design. The mosque was in falling into disrepair when the Aga Khan Cultural Service of Pakistan (AKCSP) stepped in to renovate and save this mosque. The AKCSP helped train locals in traditional, and highly specialised restoration and it also meant the mosque could be used again by the community.

The second mosque we visited was the Amburiq Mosque, 800 years old. According to the sign outside the mosque it was built by Irani craftsmen travelling with a Persian Sufi saint, Mir Syed Ali Hamdani. Again, you can see Kashmiri, Tibetan and Persian designs in the building with another lovely Tibetan tower on the top. The mosque is another example of the award winning work of the AKCSP with funding from the Norwegian Government.

The Aga Khan Cultural Service of Pakistan should be commended for the restoration work they undertake, saving historical buildings in ways that benefit the community through skills training and preserving Pakistan’s rich and varied history.

Upper level, Khilingrong Mosque

Front facade, Khilingrong Mosque

Entry, Khilingrong Mosque

Front door, Khilingrong Mosque

Amburiq Mosque, front entry

Side view, Amburiq Mosque

Layer upon layer of restored woodwork, Amburiq Mosque

Front entryway, Amburiq Mosque

Front door, Amburiq Mosque

Inside Amburiq Mosque

Window detail, Amburiq Mosque

Inside Amburiq Mosque

Postcard from Shigar Village - cricket, polo, goats, ducks, horses, washing and water - a wonderful walk

We needed to stretch our legs after a long time sitting in the car and so we decided to take a walk around Shigar Village. The village sits in the beautifully green Shigar Valley, surrounded by mountains with the Shigar River running through the valley. Shigar Village sits at an elevation of 2,230m and is inhabited by the Balti people of Tibetan descent. It is unsure where the name Balti came from however Baltistan is Persian for land of the Baltis.

Our walk took us through the centre of the village, past mosques (the subject of my next blog), shops, colourful houses, women washing, goats grazing and kids playing cricket. I love that wherever we travel in Pakistan we always see children playing cricket and it reminds me of home. We also sat and watched some children playing a version of polo. They ran with polo mallets, expertly hitting a ball across the polo ground. Polo is very popular in Gilgit-Baltistan with every valley seeming to have a polo ground.

Water channels run through the village to direct water to fields and for household use. Women sat and washed clothes or washed dishes. It is a very conservative region and the women didn’t want their photo taken. I did take some lovely photos though of shopkeepers, grandfathers and horse riders who stopped just for me.

I love this colour and you can find it painted on walls and houses

The local barber shop

Washing hung above a stream

Shigar Polo Ground - cricket being played

Practicing polo

Love that he was taking his grandson around the village for a walk

Postcard from Shigar Fort

After a very long day driving along the Karakoram Highway (see my previous blog on this amazing drive) we arrive in Shigar. We are staying at Shigar Fort. We stand in the garden of the fort and the gentle buzzing of bees in the blossoms and bleating of goats in the village below is in peaceful contrast to the last nine hours of danger and dust.

Shigar Fort was built in the 17th century and was once the residence of the Raja of Shigar. It is known locally as ‘Kong-Khar’ or ‘Fort on Rock’ as the original fort was built around a cone shaped rock. The fort now consists of three buildings built close to each other. The oldest structure is over 400 years old. The other two buildings were built around 100 and 150 years later. The fort was restored by the Aga Khan Cultural Service Pakistan from 1999 to 2004 and was then bought by the Serena Hotel chain. We were fortunate enough to be staying in one of the oldest rooms in the original fort. Standing outside the fort it is easy to see the building method of alternating stone and wood. Inside you can see Kashmiri door and ceiling details.

The fort sits in tranquil gardens with one garden offering relaxed outdoor seating and dining and another with a baridari. A baridari is a pavilion with usually twelve doors (bara is Urdu for twelve and darwaza is Urdu for door) to let air flow through. The Shigar Fort baridari is surrounded by an ornamental pond. It looks beautiful and would have been a perfect setting for the Raja to enjoy music, poetry or somewhere cool to sit.

Shigar Fort, a place to slow down, relax and be treated like a Raja.

Shigar Valley, we arrive as the sun begins to set

Shigar Fort from one of the gardens

Entrance to the hotel, in the middle of the photo you can see the cone shaped rock, where the fort gets its local name

These are the stairs leading up to our room

A day bed

The restoration has been done so well

View from our room

The baridari

View from inside the baridari

What a spot to have breakfast

View from the top of the fort

Postcard from the Karakoram Highway ‘life is a journey not a destination’

We are driving along the Karakoram Highway from Hunza, through Skardu to Shigar in Gilgit-Baltistan. It seemed like a good idea to drive, to see more of Pakistan, to experience what has been described as the eighth wonder of the wonder. I also wanted to continue our journey along the Old Silk Road.

This section of the Highway is 325 kilometres and according to Google maps will take 7 hours to drive. Our guide mentioned it was more likely to take 8 to 9 hours depending on road conditions and road works.

The Karakoram Highway, also known as the China-Pakistan Friendship Highway is 1,300 kilometres in length and starts in Hasan Abdal in the Punjab Province and ends at the Khunjerab Pass in Gilgit-Baltistan (the subject of a previous blog). Started in 1959 and finished in 1979 it is one of the highest paved roads in the world. From the Highway you can see three mountain ranges, The Hindukush, the Himalayas and the Karakoram. As part of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor the Highway is being upgraded. In the building of the Highway 810 Pakistanis and over 200 Chinese workers have lost their lives due to extremely difficult working conditions.

I had been told that the journey along the Highway is spectacular but also that the road conditions can be very difficult. Work to upgrade this stretch of the Highway is underway, with impossibly large equipment scattered along side the road. The Highway moves from a single paved road to a double paved road (it still looked like a single road to me), to gravel, and back to being paved again. Landslides are a common occurrence. A large portion is still gravel, with no guard rail and a steep drop to the valley below.

Being forewarned didn’t prepare me for how difficult parts of the road were to drive along. The single laned parts of the Highway made me grip the handle of the passenger car door and breath in when cars and trucks tried to pass. The gravel threw up lots of dust and at times it was difficult to see the road ahead. When a truck broke down on a tight, single lane, hairpin turn I thought we were in for a long wait. I was more horrified when our driver decided to edge slowly around the truck. Local workers were extremely helpful helping us navigate around the truck, but I was then also concerned for their safety.

When the road widened and was smooth, I could sit and enjoy the passing scenery. We would turn a corner and in front of us would be the most beautiful green valley with neat terraces climbing high up the mountainside. We would turn another corner and see mountains rising high above us. Another turn brought back my fears as I saw the remains of a large landslide flowing down the mountain. One of the most spectacular sights was Nanga Parbat, at 8,126 metres. Nanga Parbat stands at the western end of the Himalayas, it is the ninth highest peak in the world. There are fourteen mountains in the world that are 8,000 metres or higher, five are located in Pakistan.

There is a quote, attributed to Ralph Waldo Emerson, that ‘life is a journey not a destination’. The Karakoram Highway is a spectacular, if somewhat terrifying, journey.

Leaving Hunza

Nanga Parbat in the far distance

Nanga Parbat a little closer

Part of the newly sealed Highway

Stopping for a rest and watching the trucks and vans drive past

Small truck about to leave to continue their journey

The dusty edge of the Highway

Road workers taking a break

Small tents along the Highway to house workers

So much dust it was hard to see the road

Trucks approaching

My view of a truck from my passenger seat

The dusty road winds on

Landslide, thankfully across from the road

Goats ignoring the stop, blast area, sign

Zig-zag path of the Old Silk Road

Rocks, stones and dust

The edge of the Highway. The strings you can just see are mapping out future road works

Building a retaining wall and bridge

New retaining wall and man hanging off the back of a small truck

Still hanging on

Suddenly it turns green

Amazingly green fields after hours of dust

Skardu Valley, where the Indus and Shigar rivers meet

Postcard from Passu - a glacier, a cathedral, a bridge

After leaving the Khunjerab National Park we head back to Hunza, stopping in Passu. Pakistan has over 7,000 known glaciers and contains more glacial ice than any other country outside the polar regions. Pakistan has a population of over 220 million people who rely on glacial water for drinking water and farming. However, Pakistan’s glaciers are receding. Rapid glacial melt has lead to flash flooding, avalanches, landslides, destruction of infrastructure and loss of life.

In the south of Passu is the Passu Glacier. This glacier links up with a number of other glaciers in the region. The Passu Glacier is 20.5 kilometres long, spread over 115 square kilometres. Behind the glacier sits Passu Peak at 7,478m.

The view from the road is breathtaking, on the left is the Passu Glacier and on the right is Tupopdan, also known as Passu Cones or Passu Cathedral. This mountain range stands at 6,106 metres above the Hunza River. Tupopdan is the local name for the mountains and it means ‘sun gulping mountains’ but as we were there on a very cold and overcast day I will have to believe the locals. The sharp peaks made me think of a sleeping dragon, but I could also see the reference to cathedral spires.

We had also stopped in this area to see and perhaps walk across the Hussaini Suspension Bridge. It is a pedestrian bridge that crosses the Hunza River so you can walk to Zarabad Hamlet from Hussaini Village. The Bridge has been washed away a number of times due to flash flooding. It is made of wooden planks, some narrow, some wide, each plank is set at a different width to its neighbour making it very difficult to walk with confidence. It also moves up and down as other people cross the bridge and swings side to side in the wind.

I slowly stepped out onto the bridge, it moved slightly side to side, I kept walking and when someone walked closely behind me the bridge moved up and down and I felt like I was on a trampoline. I waited until they had passed by and kept walking, slow by slow step, holding tightly to the metal wires. As you move further along and further out over the river the bridge moves a lot more, but I was gaining in confidence and started to walk a little bit quicker. I made it to the other side and was feeling pleased with my daring walk only to see two locals quickly walk across the bridge without holding on! I was so fascinated with their progress I forgot to take a photo of them.

I turned around and walked back across the bridge, I was happy to have walked across and even happier to be back on safe, non-rocking ground.

On the far left is Passu Glacier with the Passu Cones in the centre

Passu Glacier

Tupopdan, also known as Passu Cones or Passu Cathedral

Our first view of the Hussaini Suspension Bridge

Looks much longer up close

Ready to start

View from the opposite bank

Steps leading up to Zarabad Village

Some thick planks and some exceptionally thin ones

I’ve made it back!

Postcard from the Khunjerab Pass

The road disappears under snow and ice

We are driving 182 kilometres from Hunza at an elevation of 2,438m, along the Karakoram Highway, to the Khunjerab Pass at the Chinese Border. We will be driving through the Khunjerab National Park at an elevation of 5,200m. The upgrading of the Karakoram Highway is part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.

Our first stop is at the exceptionally blue Attabad Lake. The lake was formed in January 2010 as a result of a landslide. Twenty people were killed and villages disappeared under water. The Hunza River was blocked for five months. The Karakoram Highway was moved and five tunnels were built named the Pak-China Friendship Tunnels. The longest tunnel is over 3,000m. Today the Lake is used for boating and fishing.

After the tunnels we enter a world of muted colours, of grey rocks and skies, of white snow and blue ice. I am surprised at how quickly the landscape changes, it seems that winter is still here. I find the stark landscape very beautiful, but the winds are bitterly cold.

We have been told that the Khunjerab National Park is open to visitors and we should be able to make it to the border. However, we are warned to be extra careful as the day before a 4WD had come off the road. As spring comes to this region the snow melts and ice forms making the roads dangerous.

The National Park is known for its wildlife: yaks; snow leopards; Marco Polo sheep; ibex; marmots; lynx; wolves; foxes and numerous birds. It covers an area of over two thousand square kilometres. There are some trees that seem to be able to flourish in the snow: juniper; birch; willow and poplar. Trees soon give way to low bushes and then low grasses. We stop and watch herds of yaks move slowly, looking for grass. They don’t mind having their photo taken. The ibex are lot more skittish and run and jump out of our way.

We drive slowly up the winding road that is wide and well maintained. Soon the road becomes difficult and disappears under snow and ice. Within two kilometres we give up hope of reaching the Chinese Border. The snow is too thick, and we can’t see the edges of the road ahead. Time to turn around and head back to Hunza. On the way down we see a flash of orange. I think it is a fox, but we are told it is a golden marmot, a lucky, rare sighting. We watch as it moves with surprising speed across the steep and icy slopes. On the way home we stop at the Hussaini Suspension Bridge, the subject of my next blog.

We return to the mild, green, and blossom filled Hunza Valley. It has taken a day to not reach the Chinese Border but it has been another day filled with adventure, beauty and wonder.

Attabad Lake

One of the Pakistan-China Friendship Tunnels

As we pass through the tunnels and come out the other side it feels like all the colour has been removed from the landscape

A photo opportunity for Geoff to wear the local cap and scarf, both are made from wool, both are very warm

There are a small number of suspension bridges crossing the Hunza River, this one is for cars

We watch as the black 4WD crosses over the bridge

We stop so I can photograph these beautiful Birch trees

Unconcerned Yak

He lifted his head and seemed to say ‘take my portrait please’

Ibex

What you don’t want to see at the side of the road

We stop for a very quick selfie and then jump back into the warm car

Golden marmot

Postcard from Baltit Fort

When you first arrive in Hunza you can see Baltit Fort sitting high above the valley with a wondrous backdrop of snow-covered mountains. It is close to Altit Fort (the subject of my previous blog) but where Altit sits next to the Hunza River, Baltit Fort seems to float in front of the mountains and the Ultar Glacier.

Be ready for a steep climb through the town of Karimabad to reach the entrance to Baltit Fort and then be ready to climb more steps to get to the front door and yet more steps inside. The effort is worth it. Baltit Fort is an impressive building with even more impressive views of the whole Hunza Valley.

The site was obviously chosen for its strategic importance for security, water and trade. The Fort was built 700 years ago on a flattened rock spur and floors and rooms have been added over time. Notable changes came about in the 16th century when the local Mir (king) married a Baltistan princess. As part of her dowry renovations were made by Balti craftsmen and you can see Tibetan influences in the shape of the ceilings and on door supports.

In my last blog on Altit Fort I wrote about two princes, Prince Shah Abbas and Prince Ali Khan and their disagreement that led to the death of the younger prince. Prince Shah Abbas made Baltit Fort the new seat of power for the region. It remained the palace until 1945 when the Mir built a new palace close by.

Left empty and in need of serious repairs there was concern that the Fort would become a ruin. Six years of renovations were completed in 1996 by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture. The renovations have been done exceptionally well and have kept the original feel of the Fort. From the soot stained and charred ceilings in the kitchens to the colourful mosaic windows open to the cool wind from the surrounding mountains you can start to imagine what life must have been like here.

Baltit Fort at the foot of the Ultar Glacier

Baltit Fort sits on a flattened spur of rock

Walking past traditional houses in Karimabad

History around and above every corner

Water was and still is a valuable resource. Water channels were built across Karimabad

Side view of Baltit Fort with clear lines of wood and stone

Just a few more steps to get inside the Fort

Local with traditional woollen Gilgiti cap with shaati feather

Maintenance of Fort and surrounding buildings is hard work as all stone has to be carried by foot

Cannon from 1863

View of Hunza Valley from top terrace

Tibetan inspired ceiling above the kitchen

Centuries of soot and smoke

What do you think this box was used for?

Ceiling detail

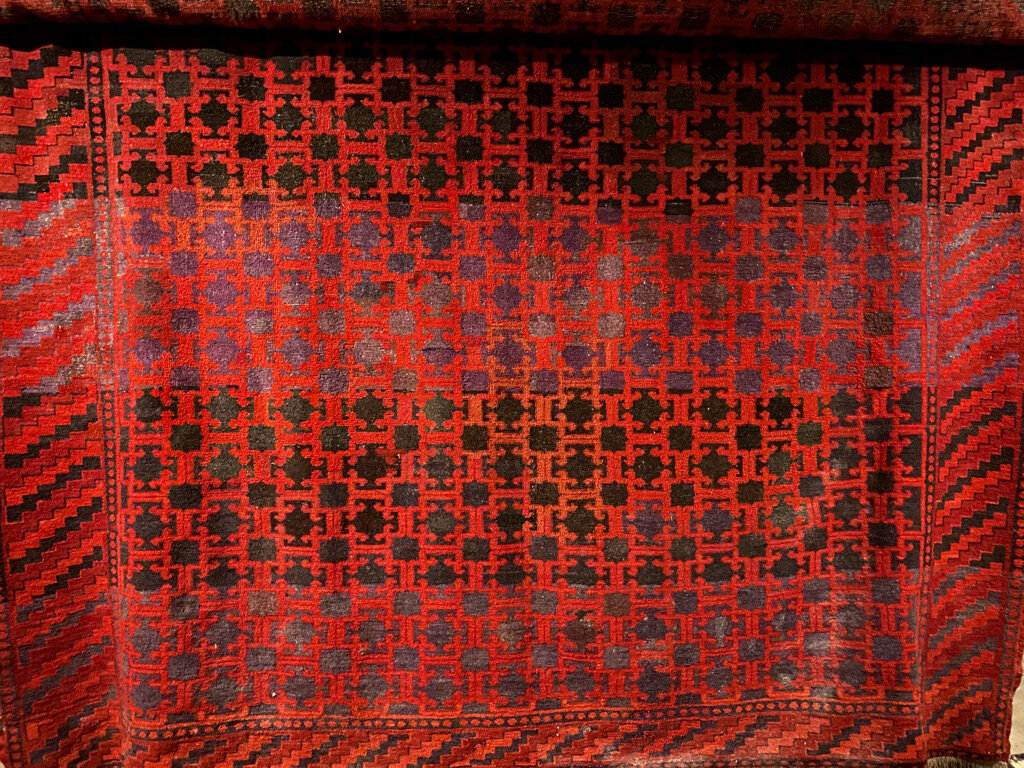

Traditional Hunza woven rugs

In the mid ground you can see Altit Fort

Postcard from Altit Fort - a thousand year old fort with a thousand foot drop

As you can see from this photo Altit Fort sits high above the Hunza River. There is a straight, 1000 foot drop from the fort to the river below. The Fort started as the traditional home of the local Mir, or king. It sits in a strategic position overlooking the Ulter Glacier and the Hunza Valley. The Fort’s prime position made sure that the Mir was ready against attack at all times.

The Fort has been wonderfully restored by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture and the Norwegian Government from 2006 to 2010. The Fort is built of wood, stone and mud. The use of alternating wood with stone made it able to withstand earthquakes. Looking up at the Fort you realise that it would be difficult to build today, let alone 1000 years ago.

Inside the Fort you can find rooms with furniture and belongings giving an idea of what life might have been like for the Mir and his family. Each room has intricately carved door lintels and window shutters. Doors and ceilings are low, windows are small to keep in the heat.

The Fort has a fascinating history revolving around princes, politics and pillars. Around 1540 a new fort, Baltit Fort, was built in Hunza (the subject of my next blog). Prince Shah Abbas moved to Baltit Fort, and it became the new capital of Hunza. Prince Shah Abbas’ younger brother, Prince Ali Khan, remained at Altit Fort. The two brothers fought and it is believed that Prince Shah Abbas buried his younger brother alive in a pillar in one of the rooms in Altit Fort. This is not the only story of death at the Fort. Altit Fort has one tower ‘Shikiari’ or ‘Hunters Tower’. Prisoners were held in dungeons and sentencing could involve being thrown from the tower over the cliff.

However today you will find it a peaceful place. After spending time looking around the Fort you can enjoy a walk through the beautiful gardens and stop at Kha Basi, a former Mir’s winter residence, now a café with great views.

As we were walking around the garden, we heard some wonderful music. Set in a corner of the garden is a music school where students can learn to sing and play traditional Pakistani instruments. We had been walking past during one of their rehearsals and were fortunate enough to be invited into the school to listen to the students play. As a bonus our travel guide and our guide from the fort got up to dance. It was a wonderful end to our visit to Altit Fort – an afternoon of history, politics, music and culture.

Altit Fort built closely around the rock base

Front door to Altit Fort

The pillar!

The kitchen

View from the top of the Fort across the Hunza Valley

Old Altit Town sitting under the Fort

Postcard from Old Altit Town

A look down on Old Altit Town from Altit Fort

A gentle walk from our hotel to Old Altit Town takes us along dusty roads, past tall poplar trees and alongside terraced farms. Land and fuel are both in short supply so poplar trees are planted because they are fast growing and don’t give too much shade over farmland.

As we walk along the road we hear a lot of shouting and clapping. As we turn a corner, we see that there is a cricket match going on. The pitch is dusty and bumpy, the bowlers fast but the batters understand the pitch and where to place the ball. Around the edge of the pitch there is a wall that is terraced, local men and boys are sitting and encouraging their favourite players. We stop and watch for a while. We are asked where we are from and the answer of Australia brings smiles for another cricket loving country. Sign language helps us understand where the boundaries lie: beyond the trees is a six; first terrace is a four.

We continue on our walk to Old Altit Town. The town sits below and right up against Altit Fort, the subject of my next blog. As we walk through the town we see a courtyard with many women sitting around chatting to one another. They are all wearing the traditional, embroidered Hunza hat, over which they place their dupatta (scarf). Read my previous blog on the Hunza Valley if you want to see one of these hats up close.

I ask if I can take some photos. The rest of my group, all men, are not allowed in. I walk around smiling and saying hello, my Urdu is poor, they don’t know English. As I point to my camera some agree to have their photo taken. One woman points to her face and from her expression seems to say why would I want to take her photo. I nod and smile, she smiles and agrees to have her photo taken – it is my favourite portrait that I have taken in Pakistan. I would like to stay but my group is waiting, I say my goodbyes. They laugh and keep talking. After a long day working it is wonderful to see them taking a moment to sit and chat with their friends.

Green poplars, dusty roads, surrounded by mountains

Local cricket pitch - unforgiving surface!

A fellow cricket lover who was happy to help out with questions on boundaries.

Small cobbler business

Chicken shop - didn’t stay to see a purchase

Central pond in Old Altit Town. This pond freezes over in winter.

Gateway to the women’s courtyard

Language may have been a barrier but we all smiled and laughed

Old Altit Town

Looking down into Old Altit Town from Altit Fort. You can just see part of the women’s courtyard in the top, left corner

Houses made of wood, mud and mud bricks, small courtyards and gardens, flat roofs for sitting, washing and water tanks

Postcard from the Hunza Valley

Beautiful blossoms and snow capped mountains will be my lasting impression of the Hunza Valley

The Hunza valley is in the northern part of Gilgit-Baltistan at an elevation of 2,438 meters. Afghanistan is to the north and China is to the northeast. The Hunza River runs through the valley and you can still see remains of the Old Silk Road.

We visited during spring and the apricot blossom trees were in full bloom. The air was fresh, villages clean and terraces beautifully ordered. It was wonderful to walk along nearly deserted paths and hear nothing but the buzz of bees and the occasional motorbike.

In 1933 a novel by James Hilton was released called ‘Lost Horizon’. In 1937 it was made into a film by Frank Capra. The book and film are set in Shangri-La, a ‘mystical and harmonious’ valley in Tibet that is isolated and where people live for hundreds of years. It is thought that Hilton based his novel on the location and people of the Hunza Valley.

The Hunzakut were rumoured to live exceptionally long lives, to be very fit, to be vegetarian and never get ill. Unfortunately, this has turned out not to be true. The Hunzakut are very fit as most must walk to work in the fields, at altitude. During the summer they do follow a mostly vegetarian diet as the growing season for fresh fruit and vegetables is very short. Animals are kept for meat for during the long winter months. As Hunza is very difficult to reach a lot of diseases did not arrive until roads opened up the valley. As to living very long lives this depends on how you measure age. Apparently the Hunzakut do not measure age solely by years but also by wisdom.

If you are ‘wise beyond your years’ you will visit Hunza as it is a beautiful place filled with stunning landscapes and hospitable people.

Hunza Valley from Altit Fort

Hunza Valley panorama taken from Altit Fort. Hard to give you a sense of being surrounded by mountains

Hunza Valley from Baltit Fort

Snow gives way to barren mountain sides. Those squiggly lines in the middle are roads going up high into the mountains.

The Hunza River runs through the centre of the valley

Blossoms above and below

Poplar trees and patchwork terraces

A man rests and checks his phone

Pink blossoms against a blue sky and white snow capped mountains

Clouds lift and we can see the mountains from our hotel

Delicate apricot blossoms

The day ends, the sun sets, we watch the changing light on the mountains.

Postcard from Rakaposhi

Today we drive from Gilgit to Hunza, just over 100 kilometres along the Karakoram Highway. We are looking forward to seeing a number of mountains: Rakaposhi; Diran Peak; Hunza Peak; Ulter 1 and 2; and Dastgil Sar Peak.

This part of the Highway has been completed and is smooth but sometimes very narrow. There are a number of memorials along the highway to honour the workers who died building it. We stop at one memorial and meet the custodian who tells us about the workers who died building this stretch of the Highway. The inscription reads ‘In memory of their gallant men who preferred to make the Karakorams their permanent abode’ 1966-1972.

Our next stop is to see Rakaposhi, a mountain in the Karakoram Mountains about a two hour drive north of Gilgit. At 7,788m it is the 27th highest mountain in the world or the 12th highest mountain in Pakistan. Despite only coming in at 27th, well behind K2, this mountain is loved in Pakistan and we were keen to see it up close.

Rakaposhi means ‘snow covered’ locally but the mountain is also called Dumani ‘Mother of Mist’ or ‘Mother of Clouds’. We had an exceptionally clear day and there was only the faintest hint of a cloud around the summit. Ragaposhi is situated in the Nagar Valley and as we drove along the Karakoram Highway we kept seeing enticing views.

The place to get the best views of Rakaposhi is at the Rakaposhi Viewpoint in Ghulmet where we stopped for morning tea. According to the sign at the viewpoint we were at 1,950m and we could see the highest, unbroken slope on earth. The summit is almost 6 kilometres above us and only 11 kilometres away. It is the only mountain on earth that plummets directly, uninterrupted, for almost 6,000 metres from the summit to its base.

The Viewpoint has a small café and gift shop, the tea was very good, and I couldn’t resist buying a souvenir. As we were travelling during Ramadan we were the only ones there enjoying the spectacular scenery and peace and quiet.

Travelling along the Karakoram Highway from Gilgit to Hunza

Karakoram Highway Memorial

Memorial and cemetery custodian

Seating area next to memorial

We are driving alongside the Hunza River

Beautiful vistas keep opening up

The milky green of the Hunza River

Roadway on other side of the valley, tall Poplar trees along each ridge

Down below in the valley, terraced farms covering every available piece of land

View from our car - the road can be very narrow

At least you get to see Truck art details up close

Rakaposhi Viewpoint Cafe

My souvenir purchase - a traditional hat from Hunza - hand embroidered on cloth. Women wear them with a scarf over the top

Rakaposhi Viewpoint Cafe

Rakaposhi

A final road stop before continuing on to Hunza

My favourite view of Rakaposhi, terraced farms, flags flying in the wind